City Forgotten: The fate of small towns in India's urbanization

THIS ARTICLE WAS FIRST PUBLISHED IN OPENDEMOCRACY ON 18TH SEPTEMBER 2013. CLICK HERE TO SEE ORIGINAL ARTICLEhttp://youtu.be/vJRLRdcujBc

Late one evening, my academic partner Abdul Shaban, his research assistant Noor Alam and I reached Malegaon in a hired car via a long dusty road off the Mumbai-Nashik highway. We lost our way several times even though both Shaban and Noor Alam had been to Malegaon several times earlier, but the nondescript nature of the road and the journey through fields and industrial setups in the dark can confuse anyone. We reached Malegaon finally by asking local passers-by, who assured us that this was indeed the road to the infamous town.

Malegaon can be presented as a poster-child of deprivation and marginalization. A medium sized town with close to half a million population and about 100 km from Nashik in Maharashtra, Malegaon's economy is driven mainly by its power-loom industry. The Census notes that Malegaon has over 80 percent Muslim population, over 50 percent population living in slums, and over 50 percent of the population under the poverty line. There is extremely low rate of paid employment among women and till very recently women were also much less educated than men in the town (Shaban 2011). While its neighbouring textile-industry based towns such as Ichalkiranji, Solapur and Bhiwandi have become prosperous through various state schemes for industrial development, Malegaon has remained largely bereft of these benefits. A continuous (mis)representation of Malegaon in the media as a place of communal riots, which reached its head after a series of bomb blasts in 2001 and 2006 has sealed its fate as a 'troubled' town. How were Malegaonkars coping with these wider politics of representation and insecurity? Why was Malegaon not 'developing' as other neighbouring towns? Was the state responsible for Malegaon's underdevelopment? As we passionately debated these issues on our way into Malegaon, it also occurred to me - had we chosen Malegaon for all the wrong reasons? Would we be accused of seeking out marginalization where we can find it most? Were we 'orientalising' Malegaon by making a documentary on it?Through the eyes of its residents, local activists and civil society members, 'City Forgotten' tells the story of Malegaon’s fall from its status as the Manchester of India to a town in decline, where its women and minorities continue to aspire for and claim their constitutional rights to education despite the lack of any real prospects for its future generations.

Small and medium towns: Gendered casualties of India's urbanization

Malegaon has been systematically denied its due share of investment and development from the state and private sector. India's recent Census count has labelled Malegaon as a 'class I town', which means that it was entitled to a governance structure and administrative setup of a city. It implies that Malegaon as a newly recognized 'urban' area should ideally have benefited from investments in infrastructure and employment. But so far it has been one of the main casualties of India's rapid economic growth and urbanization initiatives.Indeed most rapidly expanding urban areas of megacities such as Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata and so on have expanded through huge public-private initiatives, private sector investments and infrastructure development programmes. The recent focus of the Indian state on cities as engines of development and growth (Kennedy and Zerah 2008), has spurred rapid urban development across the country's small, medium and large towns and cities. McKinsey Global Institute (2010) suggests that urbanization will continue to flourish in India whereby the megacities will over time transform into some of the largest urban agglomerations in the world. In particular the Mumbai-Pune-Nashik triangle of cities, which include Malegaon is predicted to become the second largest mega-city cluster (after Shanghai) by 2050. So why has Malegaon been forgotten?There are two main reasons for this. First that Malegaon is part of a particular trend in urbanization in the global south whereby erstwhile towns and villages are rapidly expanding and 'urbanizing'. As Ghosh 2012 notes.

... in India the latest census shows that, over the past decade, there has been a huge increase in the number of urban conurbations, from 5,161 in 2001 to 7,935 in 2011, an increase of 54% that dwarfs the 32% growth in urban population. This is mainly because of reclassification of settlements from rural to urban as they start showing higher population density (more than 1,000 persons per sq km) and as non-agricultural work becomes dominant. This is highly significant since increase in areas still not officially recognised as "urban" (and therefore lacking the institutional and administrative machinery provided to urban areas) accounts for more than 90% of the increase in the total number of urban settlements.

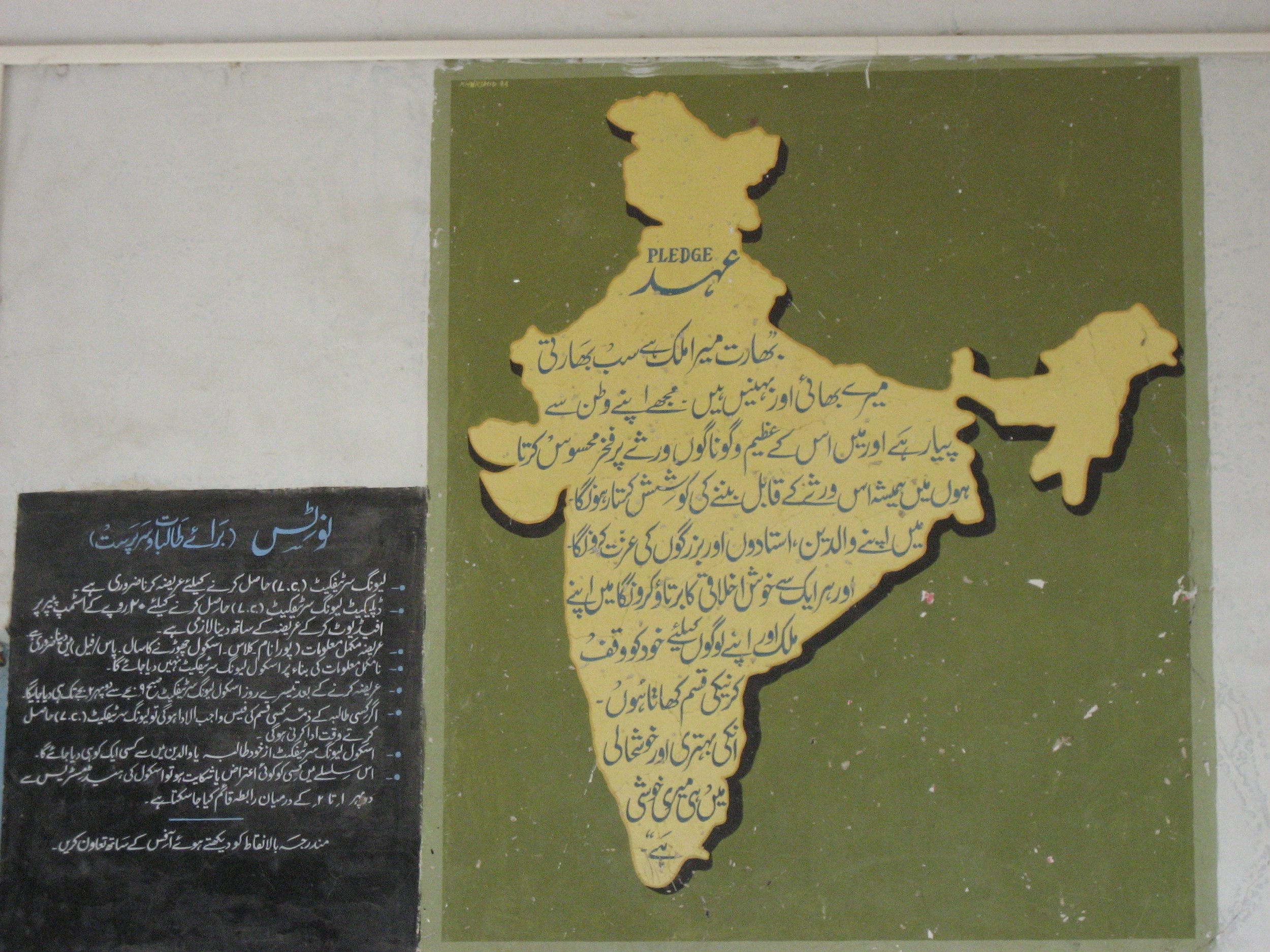

Malegaon Municipal Corporation. Photo © Ayona Datta

Malegaon Municipal Corporation. Photo © Ayona Datta

Thus although these small and medium towns have been transformed into 'cities' in their legal/bureaucratic identities, their social and physical infrastructure still remain at a rudimentary level. While India's rapid urbanization has brought 'Development' (with a capital D) into India's megacities, the urbanization of its small and medium towns has been more ad-hoc, haphazard and unplanned. As a result, India's small and medium towns have been the main casualties of its urbanization. They suffer from a lack of strong institutions of local governance, state development schemes for established urban areas and private sector investment. On the other hand continuing 'elite capture' (Kundu 2010) of land on their peripheries suggests that urban development in these small towns and cities do not usually benefit their residents. They are now characterized by the absence of local democratic institutions, poor urban infrastructure and continued loss of agricultural/forest land to development projects (Sharma 2012).

Hindu temple and Mosque co-existing for generations in Malegaon. Photo © Ayona Datta

Hindu temple and Mosque co-existing for generations in Malegaon. Photo © Ayona Datta

Second while it has rapidly expanded in population and has been reclassified as a 'class 1' town in the recent census, its reputation as a town with 'sensitive' or volatile population has meant that the private sector has not yet been attracted to the town. Malegaon faces double marginalization - both as a small town and as a Muslim majority town with a reputation for bomb blasts and communal tensions. Malegaon is a victim of uneven geographic development. But more than that, Malegaon is a victim of its own history of migration, local multiculture and working-class livelihoods. It is a victim like similar towns or cities in the West with a high proportion of ethnic/religious minorities and reputation for traditional, parochial and conservative lifestyles. For the outsider, Malegaon oozes danger, for the Malegaonkars it is home, a beautiful historic town given 'step-motherly' treatment by the state.

Malegaon street. Photo © Ayona Datta

Malegaon street. Photo © Ayona Datta

For Malegaon, this has serious gender implications. The winds of change blowing through the town have led to a heightened increase in aspirations for social mobility amongst those living there. While the powerloom sector provided for families and households living in slums before India's urban boom, simultaneous urbanization and globalization has brought renewed desire for better employment and lifestyles among Malegaon youth. This has led to large scale migration among its younger population to neighbouring cities of Nashik, Pune and Mumbai. This is a gendered migration and a gendered aspiration. Those who emigrate from the town are mainly men engaged in further education, service sector or low-paid jobs in the city. The women who are left behind, particularly young Muslim women, are now emerging as the new 'consumers' of education in Malegaon. They are unable to emigrate as single women because of familial and community restrictions on their mobility, they do not desire to engage in powerloom work which has been the traditional livelihood for the past few generations, and therefore they find that they cannot enter paid work in Malegaon in the absence of any real opportunities outside the powerloom sector.

The women students interviewed in the documentary however, were neither passive nor did they see themselves as victims. They demanded their rights as women, as minorities, and as citizens of the state through what can be seen as 'speech acts' - verbal utterances of rights through the moral rhetoric of the state. They argued that they needed to raise these issues in the public domain in order for things to get better for future generations of women in Malegaon. Their speech acts around their legal and constitutional rights to education produced forms of gendered citizenship that were subtle, subversive and yet 'real'.

Liminal civil society and local citizenship

As I write this post, India's economy is slowing down. Its currency is crashing. Each day it falls down more points under US dollars and British pounds. While it continues to free fall, one can only imagine the fate of Malegaon and other small towns in a country under possible recession. As a local reporter said in the documentary, 'Malegaon's history and future is linked with India's future', yet this linkage is marked by the privileges enjoyed by mega-cities over working-class towns, of perceived secular/global cities over parochial/communal towns. Any investment that goes into Mumbai, Pune or even Nashik is investment taken away from building sewage lines, or water supply lines or offices in Malegaon. If the Indian economy slows down and there is less money to go around, Malegaon will be truly forgotten.There is hope. A broad range of grassroots struggles in these places are working to redefine rights and justice around citizenship claims, which challenges earlier development scholarship on women and marginal groups as victims of development (Gadgil and Guha 1995, Shiva 1998). They are producing what can be seen as a liminal civil society and local forms of citizenship. These are in three different forms of struggles for - community building across religions, making claims to constitutional rights via media, and creative and parallel film-making.One of the social activists I interviewed in Malegaon is working across Hindu and Muslim communities in building relationships of trust. Engaging particularly with Malegaon youth, he works to dispel some of the popular myths about each community by engaging them in active dialogue with each other. Calling this a form of social learning and the development of 'critical consciousness' he says face-to-face conversations between young people of different faiths has gone a long way to reducing feelings of distrust and insecurity particularly in testing times such as the Mumbai or Gujarat riots.Another local reporter lobbies bureaucrats, policy makers and local politicians in attending to their rights as citizens of a class 1 town, an industrial town and a town forgotten by urbanization. He also writes for the national newspaper to highlight particular issues arising in Malegaon. Further he also maintains a website through which he disseminates news to the wider publics. Well networked and educated he is one of the few in Malegaon who does not live in slums and therefore one who has a substantial amount of social and cultural capital. to negotiate with the political elite.Finally I want to end this article with an example of one of the most creative agencies produced from some of the most abject conditions of everyday life. Mollywood, the local film industry in Malegaon produces spoofs of major hits of national or international films. This is a form of parallel film-making which relies on the local context, local labour and local resources to produce highly socially informative and activist orientated films. They have no expensive props and the actors in the film usually work in the powerlooms by day. Mollywood films debate local struggles with water, powercuts, alcohol abuse, domestic violence and so on through humour and popular entertainment. Mollywood is a relatively less known yet popular movement that uses indigenous forms of subversion and resistance through the big screen. Mollywood has recently been endorsed by a number of Bollywood and Hollywood actors and is beginning to make an increased impact on the wider world by drawing attention to local citizenship rights and duties.The future of Malegaon is one of hope, articulated by several participants in the film. A progressive future is hard work, and Malegaonkars are testament to that. The active and subversive work that each resident of Malegaon is conducting in their home, neighbourhood and city is making the state increasingly aware of the difficulties of their everyday life around basic needs such as water, sanitation, electricity, education, employment and so on. The State Minorities Department has already commissioned an in-depth study of Malegaon's potential development (Shaban 2011) and are looking into possibilities of implementing that. A progressive, inclusive and just future will not come easily but it is immanent.

References

Gadgil, M., Guha, R., 1995. Ecology and Equity: The Use and Abuse of Nature in Contemporary India. Routledge, London and New York.Ghosh, J (2012) http://www.theguardian.com/global-development/poverty-matters/2012/oct/02/challenges-urbanisation-greater-small-townsKennedy and Zerah, H. 2008. The Shift to City-Centric Growth Strategies: Perspectives from Hyderabad and Mumbai, Economic and Political Weekly, September 27, 110-117.Kundu, A. 2011. Politics and Economics of Urban Growth, Economic and Political Weekly, May 14, 10-12.McKinsey Global Institute (2010) India's Urban Awakening: Building Inclusive Cities, Sustaining Economic Growth. New Delhi: McKinsey Global Instiute.

Sharma, K. 2012. Rejuvenating India’s Small Towns, Economic & Political Weekly, vol xlvii (30), 63-68.

Shiva, V. 1988. Staying Alive: Women, Ecology and Development, London: Zed Books.Shaban, A (2011) Multi-Sectoral Development plan for Malegaon town, Mumbai: Tata Institute of Social Sciences.